December 2020

This year, we launched our Meaning Monthly newsletter to help you to unpick and understand trends and behaviours emerging from the homeware and healthcare industries. As the year comes to a close, our team have been reflecting on some of the most notable provocations and insights that have arisen from 2020, and what this means going forward.

Technology isn’t currently designed for repair. In some cases, it is even designed to fail after a certain amount of time, a process called planned obsolescence.

In a push to be more sustainable and reduce consumption, the EU commission is calling for companies to design things to be easily repairable. This also means that companies will have to allow consumers to seek repairs at a wider variety of outlets, rather than just official vendors.

This shows a significant turning point in the way we will consume products. As of 2021, all TVs, fridges, freezers, washing machines, dishwashers and lighting products exchanged in the EU market will have to meet minimum repairability requirements aimed at extending their lifetime.

This change will not only impact companies and the devices that they design, but it will also trigger a consumer shift as they become empowered to repair their own tech. As products are pushed to become even more sustainable and repairable, how will this change our relationships with technology? How might brands and experience and service providers enhance value in the repair and upgrade process to replicate the rush of a new product experience?

IoT (internet of things) refers to the way in which devices can communicate with each other by the transmission of data. By doing this, each device can direct and control other devices, without our intervention.

The number of devices available now means that we can have large ecosystems of tech within our homes, automating our spaces. Essentially, they seek to decrease the number of things that we have to personally pay attention to, through assistance and intelligence.

By implementing IoT systems and smart devices however, this shifts the relationship that we have with our homes. No longer just a sanctuary , our home becomes another automated assistant, who’s role is to address and serve our needs.

This shift may impact the sense of calm that we achieve in our homes as it will become harder to ‘switch off’. As our homes become our assistants, it may introduce a level of friction if things don’t run smoothly, or allow automated but insensitive reactions to events that require more empathetic responses. How can we make sure that this smart tech doesn’t disrupt the sense of peace we achieve in our homes?

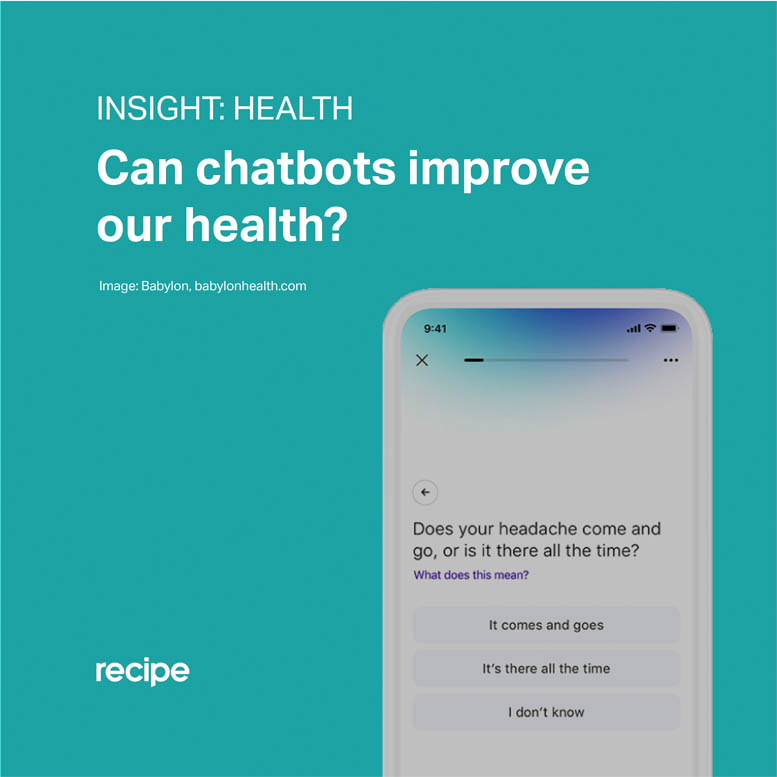

Chatbots are digital interfaces designed to simulate conversations with users. They use a pre-designed catalogue of answers in order to deliver information, answer questions and solve relatively simple problems.

Compared to their human counterpart, chatbots can store much more information, make fewer errors and can work 24/7. This makes them cheaper and faster. For these reasons alone, they are being implemented across a wide range of industries as customer assistants - one of which is healthcare.

Currently in the UK, most healthcare chatbot capabilities don’t extend much further beyond helping people to decipher their symptoms. Despite this, there is still a concern that the use of this technology in the healthcare sector could alienate people when they are unwell and need human empathy the most.

The efficiency and value of chatbots mean that their continued implementation is guaranteed and will extended beyond symptoms and diagnosis. Going forward, how can we implement them in a way that healthcare remains as humane as possible? Might an ongoing relationship with more responsive and empathetic technology allow long-term health patterns to be recognised and validated for patients, especially where pressures have reduced consistency in face-to-face healthcare provision?

As our society ages, the gap between the amount of care needed and those who are able to provide it is widening. This is particularly true for at home, long-term healthcare support, which is often overlooked in place of more emergency situations. Technology and robotics are being used to bridge the gap.

These robotics can assist with everyday support and care for those who are relatively healthy, but require a helping hand. This may include anything from devices that help with mobility and fitness, to assistance cooking and cleaning and companionship robots to ease loneliness. Their aim is to extend healthy life expectancy and help people to live independently for longer.

In situations where the care deficit is already extensive, such as in Japan, healthcare robotics are commonplace. In the UK, this tech is still in early development. So far, companies include CHIRON, who are making modular robotics to assist with routine tasks, and MiRO, a pet-like robot designed for friendship.

The question of whether robotics are a suitable replacement for human practitioners remains. Humans are social creatures bound by localised cultures, and so robotics used for social care may not be able to provide the connection necessary for adequate care and companionship for each individual. For everyday assistance with simple tasks, the use of robotics looks like a promising solution, but how can we help provide a more complete care offer?

Technology’s ability to decipher numbers and information far outshines that of humans. It can quickly analyse data, perform calculations and use this information to make informed decisions.

So far, the way in which this logic has been applied to helping us lead healthier lives has been limited. Fitness and tracking apps like My Fitness Pal allow us to access catalogues of big data, and in turn weigh out different decisions relative to our health goals.

In the future however, this technology could start to make these decisions for us. Similar to humans, it can use the catalogues of data to decide between different options. Unlike humans however, it is much faster, more efficient, and less subjective and emotive, meaning that it doesn’t give in to temptation.

This decision making ability could be applied to numerous areas of our lives, including our diets, sleeping patterns, and fitness regimes. If utilised correctly, it will allow us to be more effective in progressing towards our long-term health goals, even allowing recalibration for brief ‘blips’ in compliance. The question remains however, how much power should we give to algorithms to take control of our lives? And how can these technologies tailor advice to best suit each individual’s unique psychologies?

Previous month

November 2020

Earlier this year, we set a brief for the final year Product Design students at Central Saint Martins around the prevalence of ‘smart’ technology in our homes. The students proposed new products and experiences that critically consider ‘smartness’ and the value it provides across diverse areas of home life.

Meaning Centred Design Assessment

Meaning Centred Design helps your business understand how people think about, perceive and understand what you stand for and what you have to offer.

MCD Insights can be mapped and translated into new propositions with the potential to make your brand more distinctive, more engaging and ultimately more valuable.

This assessment is an interactive online tool that will help you quickly assess your current situation. It takes less than 5 minutes to compl